Unit 3 - The Value of Money

Learning Objective: Understand and be able to explain the value of money, how money can be devalued, and the effects of monetary devaluation on individuals, households, businesses, and economies.

Unit Outline

3.1 The Definition of Value

3.2 The Source of Value

3.3 How to Add Value

3.4 How to Devalue Money

3.5 Work and Value

3.6 Devaluation, Debasing, and Debauching Money

3.7 Measuring Inequality

3.1 The Definition of Value

Recall from Unit 1 that money serves three core functions, remembered by the acronym SUM:

- Store of Value – Preserves purchasing power over time.

- Unit of Account – Provides a standard measure for pricing goods and services.

- Medium of Exchange – Facilitates trade.

What Defines Value?

Value, as defined by Webster, means:

- Monetary Worth – The price something commands in a market.

- Fair Return – An exchange equivalent in goods, services, or money.

3.2 The Source of Value

What Makes Money Valuable?

Money derives its value from multiple sources:

- Scarcity – Limited availability increases demand.

- Utility – Practical uses create demand (e.g., food, metals, energy).

- Intrinsic Value – Built-in worth, such as gold’s rarity and durability.

- Extrinsic Value – Assigned worth, often based on perception, like art or collectibles.

- Work and Energy – The labor required to produce it adds credibility, ensuring stability and trust.

Example:

Gold and silver served as money because mining and refining them required work and energy. Their scarcity and the work needed to extract and shape them ensured they held value over time.

3.3 How to Add Value

Adding value requires work to transform raw materials into useful products.

Illustration: The Value Chain

- Wheat (farming) →

- Flour (milling) →

- Bread (baking)

At each step, work increases the usefulness and desirability of the interim product until the final product is completed, demonstrating how labor creates value.

3.4 How to Devalue Money

Devaluing money reduces its purchasing power, enabling governments to fund spending without raising taxes—or doing more work. It allows rulers to get something for nothing—at the expense of the people.

A classic example example is the Roman denarius.

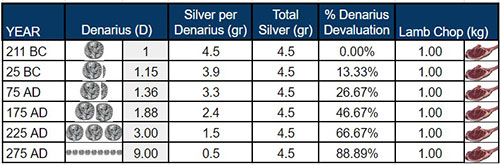

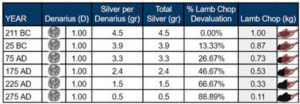

The Roman Denarius: A Case Study in Devaluation

When introduced, each denarius contained 4.5 grams of silver, and its value was tied to the work required to mine, refine, and mint that silver. The denarius started as honest money—its value backed by the labor it took to produce.

However, as the empire’s expenses grew—funding wars, welfare programs (bread and circuses), and bureaucracy—Caesar needed more money without more work. Instead of raising taxes, he debased the currency, reducing the silver content in each coin while pretending its value remained the same.

This manipulation introduced inequality by breaking the relationship between work, value, and purchasing power.

Devaluation in Action: From Equality to Inequality

Initial Value – A State of Equality:

1 denarius = 4.5g silver = 1 kg lamb chop

First Devaluation (13%):

Reduced silver content to 3.9g—producing 15% more coins without additional work.

New value: 1 denarius = 3.9g silver = 0.87 kg lamb chop.

Or: 1 kg lamb chop = 1.15 denarii (15% price increase).

➡ Inequality Introduced: 1 denarius was no longer equal to 4.5g of silver.

Second Devaluation (15%):

Reduced silver content to 3.3g—producing even more coins.

New value: 1 denarius = 3.3g silver = 0.73 kg lamb chop.

Or: 1 kg lamb chop = 1.36 denarii (36% price increase).

➡ More Inequality Introduced: The gap between stated value and real value widened further.

Final Collapse (90% Devaluation):

By 275 AD, silver content fell to 0.5g—a 90% devaluation—rendering the denarius nearly worthless.

1 kg lamb chop = 9 denarii.

Or: 1 denarius = 0.11 kg lamb chop.

Practical Lessons from Devaluation

1. Caesar Is the Source of Inequality.

- Inequality didn’t happen naturally—it was engineered by Caesar through currency debasement. By creating more money without more work, Caesar broke the equality that tied money to labor.

- Getting something for nothing is always a redistribution of wealth—from savers, workers, and producers to governments and elites.

2. Inflation as a Hidden Tax.

Devaluation diluted the value of money, forcing people to pay more for the same goods—without realizing they were being taxed.

Citizens bore the costs while rulers enjoyed the benefits of “free money.”

3. Economic Instability.

Market participants responded to inflation by:

Raising Prices to protect against losses.

Reducing Quantities (e.g., smaller loaves of bread or less meat per serving).

Hoarding Older Coins with higher silver content (Gresham’s Law).

4. Economic Collapse.

While emperors enriched themselves through debasement, society paid the price through inflation, poverty, and instability.

Trust in the currency eroded, trade slowed, and the economy collapsed—contributing to Rome’s fall.

Key Takeaway: Inequality Through Inflation Is Theft.

Devaluing money—whether through ancient coin debasement or modern inflation—creates inequality by breaking the link between work and value.

Governments get something for nothing. Citizens lose savings, purchasing power, and trust. This pattern repeats throughout history:

Rome’s collapse.

Weimar Germany’s hyperinflation.

Modern examples like Argentina, Zimbabwe, and Venezuela.

Honest money requires work, scarcity, and fairness. Dishonest currency—created without effort—destroys stability, erodes savings, and ultimately leads to collapse.

3.5 Work and Value

Money is meant to store and represent work. When money is devalued, the work it represents loses value as well. In the Roman example, the labor of miners, farmers, teachers, and artisans all became less valuable when the denarius lost its silver content.

For simplicity, let’s assume it takes 1,000 hours of labor to mine 1,000 grams of silver. Initially, each denarius might represent 270 minutes of labor (mining and minting). As the silver content declined, so did the labor value per coin:

- Initial state: 1 Denarius = 4.5 grams of silver = 270 minutes of work (60,000 minutes/222 denarii)

- After devaluation: 1 Denarius = 0.5 grams of silver = 30 minutes of work (60,000 minutes/2,000 denarii)

Did the work required to produce goods like bread or provide a service like teaching a student decrease as well? No. This mismatch between the value of money and the effort to produce goods and services creates economic distortions.

Key Insight:

Currency devaluation punishes workers by reducing the value of their labor, shifting wealth to those who control money creation—emperors then, governments today.

3.6 Devaluing, Debasing, and Debauching

Devaluation occurs when money loses purchasing power. Historically, this happened through:

- Debasing Commodity Money – Reducing precious metal content, as seen with the Roman denarius.

- Manipulating Representative Money – Changing its convertibility to commodities, such as Roosevelt’s Gold Reserve Act (1934).

- Creating Fiat Currency – Printing money with no commodity backing, causing inflation.

Historical Parallel:

- Roman Empire – Reduced silver content to fund wars and welfare.

- Modern Economies – Governments print fiat currency to fund wars, welfare, and debt, causing inflation and devaluation.

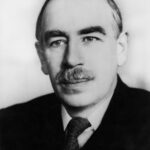

The terms devaluing, debasing, and debauching all describe the process of reducing a currency’s value. Economist John Maynard Keynes famously commented:

“Lenin was certainly right. There is no subtler, no surer means of overturning the existing basis of society than to debauch the currency. The process engages all the hidden forces of economic law on the side of destruction, and does it in a manner which not one man in a million is able to diagnose.”

(The Economic Consequences of the Peace by John Maynard Keynes, 1919. pp. 235-248.)

What did Keynes think Lenin was “certainly right” about? A few paragraphs before this, Keynes writes this:

“Lenin is said to have declared that the best way to destroy the capitalist system was to debauch the currency. By a continuing process of inflation, governments can confiscate, secretly and unobserved, an important part of the wealth of their citizens. By this method they not only confiscate, but they confiscate arbitrarily; and, while the process impoverishes many, it actually enriches some. The sight of this arbitrary rearrangement of riches strikes not only at security but [also] at confidence in the equity of the existing distribution of wealth.” (The Economic Consequences of the Peace by John Maynard Keynes, 1919. pp. 235-248.)

By inflating the currency, governments can shift wealth from citizens without them realizing it, undermining trust in the economy.

Key Insight:

Devaluing money enables governments and rulers to obtain something for nothing—often at the expense of ordinary citizens who bear the hidden costs through inflation and rising prices.

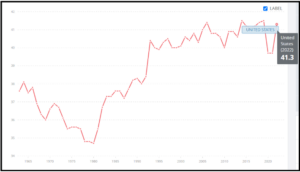

3.7 Measuring Inequality – The Gini Coefficient

Devaluation inevitably leads to economic inequality, as those who own assets benefit, while wage earners and savers suffer.

Gini Coefficient

The Gini Coefficient measures income inequality (0 = perfect equality, 1 = total inequality). Rising Gini scores signal widening wealth gaps, often fueled by inflation and monetary manipulation.

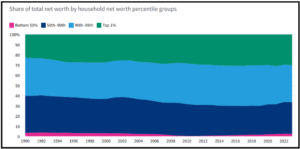

- U.S. Gini Index – Rose from 34.6 (1980) to 41.3 (2022), showing increasing inequality—almost 20%.

- The top 1% of households owns 30% of the wealth, the top 10% owns 66.6%, while the bottom 50% owns just 2.6%.

Chart: https://usafacts.org/articles/who-owns-american-wealth/

Key Insight:

Inflation and currency devaluation redistribute wealth from wage earners to asset holders, amplifying inequality and eroding social trust.

Conclusion:

The value of money is deeply tied to its ability to represent work, store purchasing power, and facilitate trade. Throughout history, money has derived its value from scarcity, utility, and trust—qualities that are easily undermined when currencies are devalued. The example of Caesar devaluing the Roman denarius highlights how monetary manipulation can erode trust, create inflation, and increase inequality, issues that remain relevant today.

Devaluing money—whether by reducing the metal content in coins, abandoning commodity backing, or inflating fiat currency—allows rulers and governments to finance wars, fund welfare programs, and stimulate economies without raising taxes. However, this process often distorts economic fairness, benefiting some groups while impoverishing others.

The consequences of such policies are seen in rising inequality, measured through tools like the Gini Coefficient, which shows increasing wealth disparities. As Keynes warned, debasing a currency can “overturn the existing basis of society” by secretly redistributing wealth, undermining confidence, and creating long-term instability.

Key Takeaway:

Money’s value is rooted in utility, scarcity, work, and trust. When governments devalue currency, whether through inflation or monetary manipulation, it distorts economic relationships, erodes purchasing power, and increases inequality. Understanding these processes equips us to critically evaluate monetary policies and their broader impacts on society.