Unit 4 - The Types of Money

Learning Objective: Understand and be able to explain the different types of money, including commodity money, representative money, fiat currency, and cryptocurrency, along with the concepts of value, work, and trust that underpin each type.

4.1 The Types of Money

Money has taken different forms throughout history, each shaped by its function and societal needs. These include:

4.1.1 Commodity Money:

- Definition: Money whose value comes from the utility of the underlying commodity itself.

- Examples:

- Soft Commodities: Things that are grown, like wheat, barley, or sugar.

- Hard Commodities: Things that are mined, like gold, silver, or platinum.

- Key Feature: The intrinsic value of commodity money is derived directly from the material itself because it requires work to produce, mine, or harvest.

4.1.2 Representative Money:

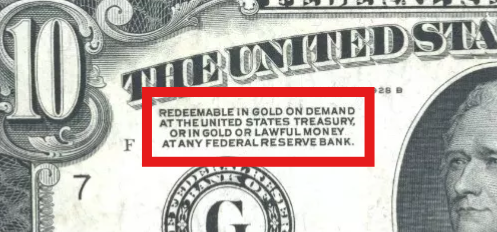

- Definition: Money backed by a physical commodity, such as gold or silver, but represented by paper certificates like banknotes—essentially a claim check on a commodity.

- Examples:

- Gold Certificates: Paper notes/certificates redeemable for gold stored in vaults.

- Silver Certificates: Paper notes/certificates tied to silver reserves.

- Key Feature: Combines portability and trust by being redeemable for something of real value.

4.1.3 Fiat Money:

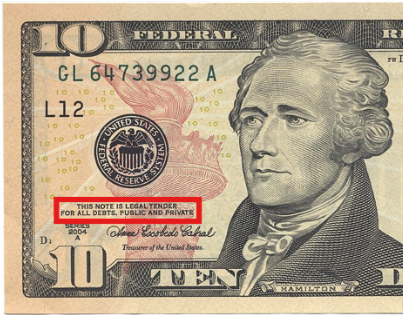

- Definition: Money without intrinsic value, established by government decree (fiat).

- Types:

- Partial Fiat: Currency backed by a commodity but not directly exchangeable.

Example: Swiss franc before 2000, with 40% gold backing. - Quasi Fiat: Currency that serves as a global reserve and is used in international trade, like the U.S. dollar (linked to the petrodollar system).

- Fully Fiat: Currency with no backing by any commodity.

Example: All national currencies today.

- Partial Fiat: Currency backed by a commodity but not directly exchangeable.

- Key Feature: Requires no work to produce, making it prone to devaluation.

4.1.4 Cryptocurrency:

Definition: Cryptocurrency is a decentralized, digital currency secured by blockchain technology—a trustless and permissionless system where transactions are verified through cryptographic algorithms rather than intermediaries like banks or governments.

- Trustless: No central authority or intermediary is required for transactions; participants rely on mathematical proof and network consensus to validate exchanges.

- Permissionless: Anyone with internet access can participate in the network without needing approval, enabling open access to financial systems.

Cryptocurrencies combine security, transparency, and programmability to offer an alternative to traditional, centralized monetary systems.

Types of Cryptocurrency:

1. Commodity-Backed Cryptocurrencies

2. Crypto-Backed Cryptocurrencies

3. Meme Coins

4. Digital Fiat Currencies

1. Commodity-Backed Cryptocurrencies:

- Description: Function like representative money, backed by physical commodities (e.g., gold, silver, or oil). These offer the stability of a tangible asset with the portability and efficiency of a digital ledger.

- Advantages:

- Tied to real-world assets, reducing volatility.

- Combines the scarcity of commodity money with blockchain transparency.

- Enables secure, borderless transactions while retaining a link to intrinsic value.

- Examples:

- Paxos Gold (PAXG): Each token is backed by one troy ounce of gold stored in vaults.

- Tether Gold (XAUT): Represents ownership of physical gold while enabling blockchain-based transfers.

- SilverCoin: Backed by silver reserves, preserving value in inflationary environments.

2. Crypto-Backed Cryptocurrencies:

- Description: Digital currencies secured through cryptographic proof-of-work or proof-of-stake mechanisms. Their value is based on scarcity, security, and market demand, rather than physical assets.

- Advantages:

- Fully decentralized and resistant to censorship.

- Trustless systems require no intermediaries, enhancing autonomy and reducing counterparty risks.

- Permissionless participation allows anyone to join and validate transactions, democratizing access to financial systems.

- Examples:

- Bitcoin (BTC): The first cryptocurrency, modeled after gold, using proof-of-work to enforce scarcity and ensure network security. Often called “digital gold.”

- Ethereum (ETH): Introduced smart contracts and decentralized applications (DApps), expanding utility beyond payments.

- Litecoin (LTC): Designed for faster transaction processing than Bitcoin while retaining cryptographic security.

- Cardano (ADA): Uses proof-of-stake for energy-efficient validation and supports smart contracts for decentralized finance (DeFi).

3. Meme Coins:

Description: Meme coins are a subset of cryptocurrencies with no intrinsic utility or foundational technology, often created as jokes or for speculative purposes. They typically lack a clear use case, security features, or long-term development goals.

Examples:

- Dogecoin (DOGE): Initially created as a joke, it gained popularity due to community support and celebrity endorsements.

- Shiba Inu (SHIB): Another meme coin, widely traded but lacking a substantive technological foundation.

- FartCoin: A recent example of a meme coin that surged 1,000% due to speculative trading, despite offering no real utility.

Concerns with Meme Coins:

- Speculative Nature: Prices often surge due to hype or online trends but lack stability or long-term value.

- No Real Utility: Most meme coins do not support meaningful projects or technological innovation.

- High Volatility: Investors face extreme risk, as values can plummet rapidly when trends fade.

- Pump-and-Dump Schemes: Meme coins are particularly vulnerable to manipulation, where early adopters profit at the expense of latecomers.

Key Insight:

While meme coins can provide entertainment and speculative opportunities, they should not be confused with legitimate cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin or Ethereum, which are built on robust technologies and serve as foundational pillars of the blockchain ecosystem.

Key Features of Cryptocurrencies:

- Trustless Systems: Transactions don’t rely on trusted intermediaries but on cryptographic proof and distributed consensus.

- Permissionless Access: Open to anyone with internet access, removing barriers to entry and democratizing finance.

- Decentralization: No central authority controls the network, reducing risks of manipulation and censorship.

- Transparency: All transactions are recorded on a public blockchain, ensuring accountability.

- Security: Cryptography protects data integrity and prevents fraud.

- Scarcity: Supply is often fixed (e.g., Bitcoin’s 21 million cap), mimicking commodity money and providing resistance to inflation.

- Programmability: Platforms like Ethereum enable smart contracts and decentralized finance (DeFi) for automated, conditional transactions.

Key Takeaways:

- Legitimate Cryptocurrencies: Crypto-backed tokens like Bitcoin and Ethereum emphasize decentralization, security, and technological innovation, representing the future of digital finance.

- Commodity-Backed Cryptocurrencies: Combine the trust of physical assets with blockchain portability, offering an innovative hybrid of traditional and digital systems.

- Meme Coins (Shitcoins): Speculative, volatile, and often lacking meaningful purpose, they highlight the need for caution and critical evaluation in the cryptocurrency market.

By distinguishing between legitimate cryptocurrencies and speculative meme coins, we can better evaluate their roles and risks within the evolving monetary ecosystem.

4. Digital Fiat Currencies

Definition:

Digital fiat currency refers to any digital representation of traditional fiat money, but it falls into two distinct categories:

1. Privately-Issued Stablecoins

Definition:

Stablecoins are privately issued digital currencies pegged to traditional fiat currencies, commodities, or other assets to maintain price stability. They operate on blockchain networks and mimic fiat systems but are not legal tender and rely on the credibility of the issuing company rather than a government guarantee.

Examples:

- Tether (USDT): Pegged 1:1 to the U.S. dollar, used primarily in crypto trading.

- USD Coin (USDC): Pegged 1:1 to the U.S. dollar, backed by reserves held by regulated financial institutions.

- Dai (DAI): Algorithmically managed and pegged to the U.S. dollar but backed by cryptocurrency collateral rather than traditional fiat.

Key Features:

- Blockchain-Based: Transactions occur on decentralized networks.

- Collateral-Backed: Issuers claim reserves (fiat, commodities, or crypto) to stabilize value.

- Semi-Decentralized: Some stablecoins operate on decentralized platforms but rely on centralized issuers.

- Counterparty Risk: Stability depends on the issuer maintaining reserves and honoring redemptions.

Concerns:

- Regulatory Uncertainty: Subject to evolving laws and oversight.

- Transparency Risks: Questions about whether reserves are adequate to maintain 1:1 pegs.

- Freezing or Blacklisting: Issuers can block transactions, undermining decentralization principles.

- Bankruptcy Risk: Private issuers, unlike governments, may fail, putting reserves at risk (e.g., FTX collapse).

2. Government-Issued CBDCs (Central Bank Digital Currencies)

Definition:

CBDCs are government-issued digital currencies that function as legal tender and are fully backed by the central bank. They represent programmable money designed to complement or replace physical cash, combining government control with digital efficiency.

Examples:

- Digital Yuan (e-CNY): China’s operational CBDC used in both domestic and cross-border transactions.

- Digital Euro: Proposed by the European Central Bank for improved payments and monetary control.

- FedNow (U.S.): While not a full CBDC, this system sets the stage for faster digital payments and possible CBDC implementation.

Key Features:

- Centralized Control: Issued and monitored by governments and central banks.

- Programmable Features: Allows for conditional spending (e.g., expiration dates, restrictions on usage).

- Legal Tender: Officially recognized as currency, unlike stablecoins.

- Financial Inclusion: Targets the unbanked population through mobile technology.

- Transparency & Surveillance: Enables full traceability of transactions, raising privacy concerns.

Concerns:

- Privacy Risks: Governments could track spending, impose restrictions, or freeze accounts.

- Negative Interest Rates: Enables central banks to impose negative interest rates directly on deposits, discouraging saving.

- Loss of Financial Freedom: Programmable features could limit how, where, and when money is spent.

- Centralized Authority: Reinforces government control, undermining decentralized principles of monetary freedom.

4.1.5 Key Differences Between Stablecoins and CBDCs

Key Takeaways

- Stablecoins act as a bridge between fiat and cryptocurrency, providing blockchain portability but relying on private issuers, making them vulnerable to counterparty risk.

- CBDCs combine fiat legitimacy with digital innovation, offering government-backed security but at the potential cost of financial privacy and personal freedom.

- Stablecoins and CBDCs may coexist, but CBDCs pose risks of centralized financial control while stablecoins maintain elements of market-driven flexibility and competition.

- Both types of digital fiat currencies highlight the ongoing debate between financial efficiency and autonomy in the digital age.

4.1.6 Legislation to Block CBDCs in the U.S.

Growing Opposition:

In response to rising concerns about government overreach, privacy violations, and financial surveillance, several lawmakers have proposed bills to block the implementation of CBDCs in the U.S.

Key Legislative Proposals:

- CBDC Anti-Surveillance State Act (2023):

- Sponsored by Rep. Tom Emmer (R-MN) to prohibit the Federal Reserve from issuing CBDCs directly to individuals.

- Focuses on protecting privacy and financial freedom by limiting government control over digital payments.

- Senator Ted Cruz’s CBDC Ban (2023):

- Proposes a complete ban on CBDCs to prevent the federal government from implementing a surveillance-based monetary system.

- Emphasizes the constitutional right to privacy and freedom from government financial coercion.

- State-Level Legislation:

- Florida and Texas have introduced laws to block the acceptance or use of CBDCs within state jurisdictions.

- These efforts highlight concerns about centralized tracking and economic manipulation at the federal level.

- CBDC Anti-Surveillance State Act (2023):

Arguments Against CBDCs in the U.S.:

- Surveillance State Concerns: CBDCs could be weaponized to monitor and control spending, similar to China’s social credit system.

- Loss of Financial Privacy: Eliminates anonymity associated with cash transactions.

- Constitutional Questions: Raises debates about the Fourth Amendment and protection against unreasonable searches.

- Financial Tyranny: Critics fear CBDCs could lead to centralized economic coercion, including the ability to freeze funds or block dissenters.

Key Takeaways:

- CBDCs represent programmable government-issued money, enabling greater efficiency but risking privacy violations and centralized control.

- Proposed U.S. legislation highlights growing opposition to CBDCs, reflecting public concerns about surveillance, financial coercion, and constitutional freedoms.

- While proponents view CBDCs as a tool for modernization and financial inclusion, critics warn they could lead to authoritarian economic controls similar to those seen in China.

The outcome of this legislative debate will shape the future of monetary systems and determine whether the U.S. maintains financial freedom or adopts centralized control mechanisms.

4.2 The Definition of Money

Recall from Unit 1 that money must fulfill these three core functions:

- Store of Value – Preserves purchasing power over time.

- Unit of Account – Provides a standard measure for pricing.

- Medium of Exchange – Simplifies trade by replacing barter systems.

Additionally, money requires work to produce—whether farming wheat, mining gold, or validating cryptocurrency. This work creates scarcity and stability, protecting value.

4.3 The Definition of Currency

According to Merriam-Webster, currency is defined as “something that is in circulation as a medium of exchange.”

4.3.1 Clarifying Fiat Money vs. Currency:

Fiat money is declared legal tender by government decree—it has value because the government says so. The word “fiat” comes from Latin, meaning “let it be done” or “by command.”

Key Distinction:

When referring to fiat systems, the correct term is currency, not money. Unlike true money, which has intrinsic value and requires work-based production, fiat currency derives its value solely from government decree and public trust.

Moving forward, we will use the proper terminology—“fiat currency” instead of “fiat money.”

4.3.2 Examples of Representative Money vs. Fiat Currency

Explanation: Backed by physical gold, this note had intrinsic value because it could be exchanged for a commodity that required work to produce.

Explanation: After the U.S. ended the gold standard in 1971 (explored further in Unit 5 – The History of Money), Federal Reserve Notes became fiat currency, severing the link to physical commodities.

4.3.3 The Evolution of Currency: From Money to Fiat

Historical Shift—From Work to Decree:

Originally, Federal Reserve Notes functioned as representative money, backed by gold or silver stored in vaults. This ensured scarcity, work-based production, and intrinsic value—qualities required for moral money.

In 1971, the U.S. abandoned the gold standard (known as the Nixon Shock), transforming the dollar into fiat currency—a claim on future productivity rather than an asset-backed store of value.

Confusion or Deception?

Because Federal Reserve Notes look the same before and after 1971, many people failed to realize the fundamental change in the monetary system. The currency retained its outward appearance but lost its backing—relying entirely on trust and government decree rather than work-based value.

The following chart shows the currency (what “circulates” as money) that corresponds with each type of money:

4.3.4 Why Fiat Currency Isn’t Money

Fiat currency fails the key tests of money because:

- No Intrinsic Value – It’s just paper (or digital entries) with no inherent worth or intrinsic value.

- No Scarcity or Work Requirement – Governments can create it without effort, violating the principle that value must come from work.

- Fails as a Store of Value – Inflation erodes its purchasing power over time, making it unreliable for long-term savings.

- Depends on Trust, Not Work – Its value hinges entirely on faith in government rather than tangible backing like gold or silver.

4.3.5 What Fiat Currency Really Represents

Fiat currency is a claim on future productivity—essentially a debt instrument. Governments print it to borrow purchasing power from the future, indebting citizens and redistributing wealth through inflation.

Key Distinction: Money vs. Currency

- Money requires work to produce, has intrinsic value, and serves as a store of value (e.g., gold, silver, or any commodity).

- Currency is a medium of exchange but lacks intrinsic value and is often backed only by government decree (fiat).

4.4 Representative Money vs. Fiat Currency: A Deep Dive

A closer look at the differences between representative money and fiat currency reveals stark contrasts between the two currencies.

4.4.1. Representative Money – Backed by Tangible Assets

Definition:

- Representative money is a form of currency that is directly tied to a physical commodity like gold or silver.

- The note promises the bearer that it can be redeemed for a specified amount of that commodity.

Example:

Key Features:

- Intrinsic Value: Its value is rooted in the commodity backing it.

- Scarcity and Work: The commodity (e.g., gold) requires work to mine, refine, and store, ensuring scarcity and limiting inflation.

- Trust and Confidence: People trusted the currency because they could exchange it for real, tangible value.

- Limited Inflation Risk: Governments couldn’t print unlimited money without increasing gold reserves, keeping inflation in check.

Historical Examples:

- Gold Certificates – U.S. currency redeemable for gold.

- Silver Certificates – U.S. currency redeemable for silver.

- British Pound Sterling – Originally tied to sterling silver.

Advantages:

- Promoted economic discipline and stability.

- Provided global trust in the currency (gold was universally accepted).

- Prevented government overreach by limiting money creation to actual reserves.

Disadvantages:

- Limited the ability to respond to crises like wars or depressions (e.g., Great Depression).

- Gold reserves were finite, restricting economic expansion.

- Difficult to maintain during bank runs or global financial shocks.

4.4.2 Fiat Currency – Backed by Faith, Not Work

Definition:

- Fiat currency has no intrinsic value and is not backed by any physical commodity.

- Its value is derived entirely from government decree and the faith of the people using it.

Example:

Key Features:

- No Commodity Backing: The government can create as much money as it wants.

- Inflation Risk: Fiat systems are prone to currency devaluation through overprinting (e.g., Venezuela, Zimbabwe).

- Trust-Based Value: Value depends entirely on people’s belief in the government and economy.

- Central Bank Control: Monetary policy (interest rates, quantitative easing) influences value, rather than physical limits like gold reserves.

Historical Transition:

- 1933: Gold redemption suspended (U.S. went off the Gold Standard).

- 1971: President Nixon officially ended gold convertibility, transitioning fully to fiat currency (The Nixon Shock).

Advantages:

- Flexibility in Monetary Policy: Central banks can print money to stimulate the economy during recessions.

- Liquidity and Growth: Easier to expand the money supply for global trade and infrastructure projects.

- Portability and Convenience: No need to carry or store large amounts of metal.

Disadvantages:

- Inflation and Hyperinflation: Governments can overprint money, leading to loss of value (e.g., Zimbabwe, Argentina, Venezuela).

- Moral Hazard: Fiat systems promote debt and spending instead of saving and productivity.

- Wealth Redistribution: Inflation acts as a hidden tax, eroding savings and disproportionately harming the poor and middle class.

- Trust-Based Fragility: Once trust erodes (e.g., financial crises), fiat money collapses.

4.4.3 Key Comparison: Representative Money vs. Fiat Currency

4.4.4 The Moral Foundation of Money – Work vs. Getting Something for Nothing

Representative Money:

- Rooted in work—whether mining gold, refining silver, or minting coins—reflects fairness because value is earned through labor and energy expenditure.

- Symbolizes honest trade—you give value and receive value, reinforcing trust and stability in society.

Fiat Currency:

- Created without work, fiat money is something for nothing—a concept fundamentally immoral and prone to abuse.

- Allows governments to steal value through inflation, enriching themselves and special interests at the expense of wage earners and savers.

Key Insight:

- Societies built on hard work and moral money systems tend to thrive.

- Systems relying on fiat money and deception risk economic instability and decline, as seen in Rome and modern hyperinflationary collapses (e.g., Zimbabwe).

4.4.5 Trust and Stability – The Fragility of Fiat Systems

Representative Money’s Strength:

- Trust is anchored in tangible value—you can redeem gold or silver at any time.

- Governments must exercise restraint, preventing excessive debt and reckless spending.

Fiat Money’s Weakness:

- Trust is based on perception, not reality.

- If citizens lose faith in the system, the currency collapses overnight (e.g., Venezuela’s bolivar).

- It allows for endless borrowing, creating moral hazards and encouraging governments to pursue wars, welfare programs, and “bread and circuses” to appease voters.

Modern Example – U.S. Dollar:

- Once backed by gold and silver, the U.S. dollar held intrinsic value.

- After the 1971 Nixon Shock, it became fiat currency, and its value now depends on confidence rather than gold.

- With trillions in debt and rising inflation, cracks in the system are beginning to show.

Key Insight:

- Stability requires discipline, but fiat systems encourage deception, resulting in unsustainable cycles of debt, inflation, and dependency.

4.4.6 Historical Warnings – Rome’s Collapse as a Case Study

The Roman Denarius:

- Initially, the denarius contained 4.5 grams of silver, representing work and stability.

- Facing wars and welfare expenses, Roman emperors debased the currency—reducing silver content to 0.5 grams by 275 AD (a 90% devaluation).

- Purchasing power collapsed, prices soared, and trust in the currency evaporated.

- This inflationary policy led to economic collapse, wealth inequality, and ultimately the fall of Rome.

Modern Parallels – Argentina, Zimbabwe, and Venezuela:

- Argentina: Repeated currency devaluations have destroyed savings and forced dollarization of its economy.

- Zimbabwe: Hyperinflation (over 89.7 sextillion percent) reduced the value of banknotes to near zero—people resorted to barter systems.

- Venezuela: Hyperinflation exceeded 1,000,000%, wiping out middle-class savings and leading to food and medicine shortages.

Key Lesson:

- Currency debasement, whether through coin shaving (Rome) or printing presses (modern times), destroys trust and stability—eventually leading to collapse.

4.4.7 Money and Power – Fiat Currency’s Role in War and Debt

War and Expansion:

- Fiat currency enables governments to fund wars without immediate taxation.

- Roman emperors debased currency to pay soldiers and fund conquests.

- Modern governments print money to finance military operations and avoid unpopular tax hikes.

Debt and Dependency:

- Fiat monetary systems promote debt-based economies, enslaving both nations and individuals.

- Modern sovereign debt crises mirror ancient problems of excess borrowing, leading to economic servitude to foreign creditors (e.g., China).

Key Insight:

- Fiat systems encourage war, welfare states, and moral hazards, pushing societies toward economic collapse, dependency, and loss of freedom.

4.4.8 Final Takeaways – Why This Matters for Students

- Work Creates Value:

- Honest money requires work to produce, ensuring scarcity and stability.

- Fiat currency breaks this relationship, promoting debt, dependency, and inequality.

- Inflation Is Theft:

- Like the Roman denarius, fiat money loses value over time, silently stealing savings from those who work hard and save.

- History Repeats Itself:

- Ancient Rome’s collapse offers a blueprint for understanding modern monetary risks.

- “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” – George Santayana

- History offers warning signs. Understanding money, work, and value helps students critically assess modern monetary systems—and advocate for fairer, more stable alternatives.

- Ignoring these lessons risks hyperinflation, social unrest, and economic collapse.

- Moral Money vs. Immoral Money:

- Sound money systems respect natural laws—work, scarcity, and fairness.

- Fiat systems violate these principles, rewarding speculation over production.

4.6 Gresham’s Law vs. Thiers’ Law: Good Money vs. Bad Money

Gresham’s Law succinctly states that “Bad Money Drives Out Good Money”.

Coined by Sir Thomas Gresham in the 16th century, Gresham’s Law describes the tendency of bad money (overvalued or debased currency) to drive good money (valuable or commodity-backed money) out of circulation.

Historical Background and Examples:

- Henry VIII’s Debasement (1544–1551):

Henry VIII reduced the silver content of English coins, replacing it with base metals to stretch the government’s resources. As the debased coins circulated, people hoarded older, pure silver coins and spent the newer, less valuable coins first. - The Roman Empire:

The denarius was gradually debased by reducing silver content (discussed earlier). Citizens hoarded earlier, high-silver coins and spent the debased ones—leading to inflation, economic instability, and collapse. - U.S. Silver Coins (20th Century):

A modern example occurred in the United States when the government removed silver from most coins in 1965.

- Henry VIII’s Debasement (1544–1551):

- Nickels, dimes, and quarters produced before 1965 contained 90% silver and quickly became more valuable for their melt value than their face value.

- Americans hoarded older coins with higher silver content, spending only the newer, copper-nickel-clad coins, demonstrating Gresham’s Law in action.

How It Works:

- Legal Tender Laws: Governments declare debased coins or fiat currency (bad money) as equal to non-debased coins (good money), forcing people to accept them at face value.

- Rational Behavior: People hoard good money (gold or silver) and spend bad money (devalued or fiat currency) to avoid losing wealth.

- Circulation Shift: Good money disappears from circulation, while bad money dominates daily transactions.

Modern Example:

- During hyperinflation in Zimbabwe (2000s) and Venezuela (2010s), people abandoned their national currencies in favor of U.S. dollars or gold, hoarding hard assets while spending rapidly devaluing local currencies as fast as possible.

Thiers’ Law – “Good Money Drives Out Bad Money”

Named after Adolphe Thiers, a 19th-century French statesman and historian, Thiers’ Law describes what happens in the absence of legal tender laws—when people are free to choose their preferred currency.

Key Insight:

When legal tender laws do not force acceptance of bad money, good money dominates because people naturally prefer stable, valuable currencies.

Why Does Good Money Prevail?

- Trust and Stability: Good money (e.g., gold, silver, or commodity-backed currency) maintains its purchasing power over time, protecting against inflation.

- Business Preferences: Merchants prefer payment in stable money to protect their profits and avoid losses due to depreciation.

- Market Forces: In free markets, currencies compete. People gravitate toward currencies with scarcity, work-based value, and stability, rejecting bad money.

Example of Thiers’ Law:

- In Argentina, where the peso has repeatedly lost value, many businesses and individuals prefer transactions in U.S. dollars or even cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin to avoid inflation.

- Similarly, during hyperinflation in Zimbabwe, people turned to the South African rand and the U.S. dollar as substitutes for bad money.

Key Takeaways:

Gresham’s Law explains how bad money dominates circulation under legal tender laws, while good money is hoarded for wealth preservation.

Thiers’ Law demonstrates that good money drives out bad money in the absence of government mandates, as people and businesses naturally prefer stability and trust over uncertainty.

Final Thought:

Governments prop up fiat systems with legal tender laws and central bank manipulation, but history shows these systems eventually fail without the discipline imposed by commodity-backed monetary systems. The clash between Gresham’s and Thiers’ laws highlights a timeless truth—when people are free to choose, they gravitate toward systems rooted in work, fairness, and stability, rejecting schemes that rely on deception and inflation to sustain themselves.

4.7 The Hierarchy of Money (and Currency)

Money types form a hierarchy based on intrinsic value, work required, and stability:

- Commodity Money – Hard commodities like gold (most stable).

- Representative Money – Backed by commodities but portable.

- Cryptocurrency (Commodity-Backed) – Attempts to combine scarcity and portability.

- Cryptocurrency (Non-Backed) – Volatile but innovative.

- Fiat Currency – Requires trust in government, easily devalued.

- Digital Fiat Currency – Same as fiat but fully digital.

Key Question: If you worked hard for your money, which type would you prefer to be paid in?

Commodity money is the most valuable money and is therefore at the top of the money hierarchy. Representative money is commodity money with paper certificates/notes used as a medium of exchange due to better portability. The following chart shows the types of money in descending order by value:

Cryptocurrency occupies a gray area between money and currency.

4.7.1 Does Cryptocurrency Meet the Criteria for Money?

- Store of Value?

- Bitcoin proponents argue it can store value due to scarcity (21 million cap).

- Critics point out its volatility, which undermines long-term value stability.

- Verdict: Partially meets this criterion but lacks stability compared to traditional forms of money.

- Medium of Exchange?

- Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies can be exchanged for goods and services but are not widely accepted like traditional currencies.

- Verdict: Partially meets this criterion.

- Unit of Account?

- Prices are not consistently denominated in Bitcoin or crypto—most transactions are still priced in fiat currencies like USD.

- Verdict: Fails this criterion.

- Requires Work to Produce?

- YES, Bitcoin mining involves proof-of-work, which consumes massive amounts of energy.

- However, this work does not produce intrinsic value—it only secures the network. Unlike gold mining, which yields a physical commodity, Bitcoin mining produces digital scarcity based purely on mathematical trust.

- Verdict: Partially meets this criterion, but the “work” creates perceived value rather than intrinsic value tied to physical production.

- Backed by a Commodity?

- NO, Bitcoin is not backed by any physical commodity—it’s backed by trust in the code and network.

- Verdict: Fails this criterion.

- Store of Value?

Final Assessment: Currency, Not Money

While Bitcoin requires significant work (electricity) to produce, it still behaves more like fiat currency than money because:

- Its value is based on trust and scarcity, not intrinsic properties or physical backing.

- It lacks widespread adoption as a unit of account and medium of exchange.

- Its volatility makes it an unreliable store of value compared to traditional forms of money.

However, Bitcoin challenges fiat currency by reintroducing work-based scarcity into the monetary system. So, while it’s currency, it does borrow some characteristics of money, making it a hybrid concept that deserves ongoing evaluation as monetary systems evolve. Time will tell whether cryptocurrencies can maintain their worth over the long term and secure their place as real money.

4.7.2 Does a Commodity-Backed Cryptocurrency Qualify as Money?

- Store of Value?

- YES—Commodity-backed cryptocurrencies (e.g., gold-backed tokens like PAX Gold) derive their value from real-world assets stored in reserves.

- The backing commodity (gold, silver, oil, etc.) provides intrinsic value, protecting the token against volatility often seen in fiat currencies and unbacked cryptocurrencies.

- Verdict: ✔ Meets this criterion.

- Medium of Exchange?

- PARTIALLY—They can be exchanged for goods and services, but acceptance is limited. Their use is often confined to specific platforms, industries, or blockchain ecosystems rather than mainstream commerce.

- Verdict: ✖ Does not fully meet this criterion yet.

- Unit of Account?

- PARTIALLY—While commodity-backed cryptocurrencies track the value of their backing assets, most prices are still denominated in fiat currencies.

- Verdict: ✖ Fails this criterion for now.

- Requires Work to Produce?

- NO (In most cases)—Unlike Bitcoin, which relies on proof-of-work mining, most commodity-backed cryptocurrencies are issued by centralized entities that tokenize existing assets.

- BUT—Their value derives from the work required to mine or produce the underlying commodity (e.g., gold or oil).

- Verdict: ✔ Indirectly meets this criterion through the work embedded in the commodity itself.

- Backed by a Commodity?

- YES—These cryptocurrencies explicitly promise redeemability for a tangible commodity, such as gold, oil, or real estate.

- This makes them representative money, similar to gold certificates used historically.

- Verdict: ✔ Fully meets this criterion.

- Store of Value?

Final Assessment: Money or Currency?

Commodity-backed cryptocurrencies behave more like representative money than fiat currency because:

- They are backed by physical commodities that require work to produce.

- Their value is tied to the intrinsic worth of the commodity, unlike fiat currency, which is based solely on trust.

However, until they become more widely used as a medium of exchange and unit of account, they still function more like commodities than everyday money in the traditional sense.

Key Takeaway: Commodity-Backed Crypto = Digital Representative Money

While most cryptocurrencies behave like fiat currencies, commodity-backed cryptocurrencies revive the concept of representative money—a bridge between modern digital systems and traditional hard money principles. They could potentially restore trust in money by tying value back to work and scarcity, but their adoption and liquidity must expand for them to function fully as money.

Conclusion:

Money has taken many forms throughout history, evolving from commodities with intrinsic value to digital currencies backed by cryptographic security. Each type reflects humanity’s attempt to balance stability, portability, and trust in the pursuit of economic prosperity.

This unit highlighted the core distinctions between commodity money, representative money, fiat currency, and cryptocurrency—exploring how each type derives its value, maintains trust, and influences economic behavior.

Key Takeaways:

- Work Creates Value: Commodity and representative money are grounded in work, requiring effort to produce and ensuring scarcity. In contrast, fiat currency and most cryptocurrencies rely on trust, not tangible backing—making them more vulnerable to inflation and instability.

- Trust vs. Work: Representative money built trust through redeemable value, while fiat currency depends solely on government mandates and public confidence. Cryptocurrencies aim to rebuild trust through decentralization, transparency, and algorithmic scarcity.

- Morality and Stability: Honest money respects natural laws of work and scarcity, promoting fairness and economic discipline. Fiat systems, which enable “something for nothing,” risk moral hazards, inflation, and societal dependency.

- Modern Innovation: Cryptocurrencies, especially commodity-backed tokens, represent an attempt to merge the digital efficiency of modern systems with the stability and fairness of older monetary models tied to work and value.

Final Thought:

The evolution of money—from commodities to fiat and now cryptocurrencies—reveals a tension between stability and flexibility, morality and expedience. History warns us that abandoning work-based value leads to economic instability, inequality, and collapse. As technology reshapes finance, the challenge is to ensure that innovation honors the principles of fairness, effort, and trust—values essential for building sustainable and moral monetary systems.

By understanding these principles, students can critically evaluate modern currencies, advocate for sound monetary practices, and prepare for a financial future shaped by both legacy systems and emerging technologies.